I still remember the first time I “saw” crossing over, in a high school lab where we twisted two shoelaces together to mimic chromosomes trading segments. It felt like a magic trick with a very practical purpose. If you’ve ever wondered “what is crossing over in biology,” here’s the short version: it’s the exchange of DNA between matching chromosomes during meiosis, the kind of cell division that makes eggs and sperm. That swap shuffles genes, fuels genetic diversity, and even helps chromosomes separate properly. In the next few minutes, I’ll walk you through what it is, when and where it happens, how the molecular choreography works, what patterns it creates, and why errors can matter for health.

Key Takeaways

- What is crossing over in biology: the exchange of DNA between homologous chromosomes during meiosis that generates new allele combinations and promotes accurate chromosome segregation.

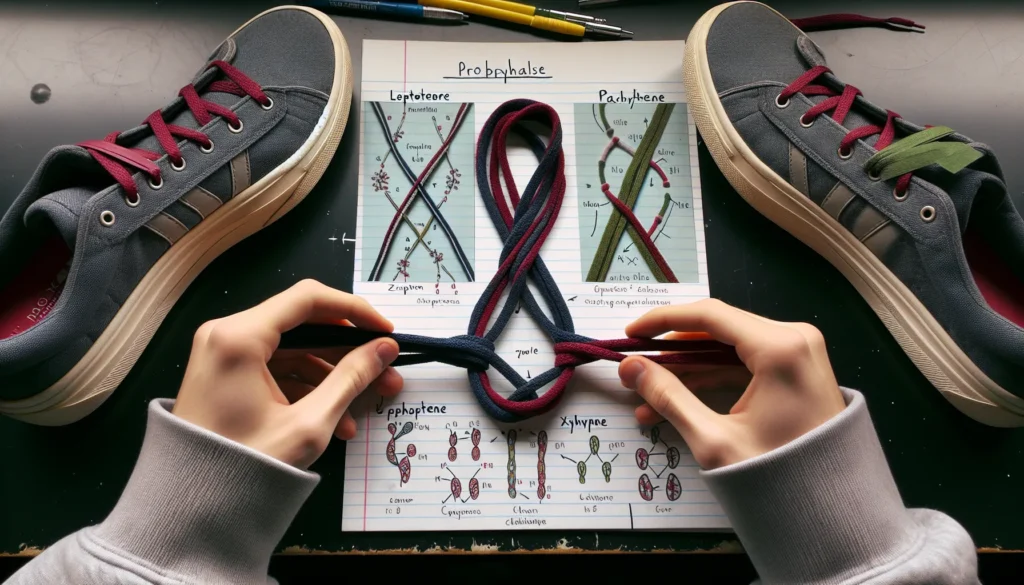

- Crossing over occurs during prophase I, especially pachytene, where chiasmata form in germ cells to physically tether homologs for proper separation.

- Spo11 creates programmed DNA breaks, Rad51/DMC1 drive strand invasion to form Holliday junctions, and enzymes resolve them into crossover or non-crossover outcomes.

- Crossover patterns follow linkage rules, are spaced by interference, require an obligate crossover, and often occur at hotspots directed by PRDM9.

- Too few or misplaced crossovers cause nondisjunction and aneuploidy (e.g., Down syndrome), while unequal crossing over creates deletions/duplications, with risks differing by sex and rising with maternal age.

What Crossing Over Is And Why It Matters

Crossing over is a precise exchange of DNA between homologous chromosomes, your maternal and paternal versions of the same chromosome, during meiosis. When these chromosome pairs line up, they physically connect and swap corresponding segments. That exchange generates new combinations of alleles (gene versions) on the same chromosome, a process called genetic recombination.

Why it matters:

- It creates genetic diversity. Siblings share parents but aren’t carbon copies, largely because crossing over shuffles allele combinations.

- It ensures proper chromosome separation. The crossover sites (seen later as chiasmata) act like tiny rivets, holding homologs together so they segregate correctly in the first meiotic division.

- It’s the backbone of genetic mapping. The frequency of crossovers between two genes tells us how far apart they are on a chromosome, measured in centimorgans.

In plain terms, crossing over answers two big biological needs at once: variety and accuracy. Variety, because mixing alleles can produce traits that help populations adapt. Accuracy, because at least one crossover per homolog pair (the “obligate crossover”) provides the tension and tethering needed for chromosomes to part ways without getting lost. Without it, fertility drops and errors rise.

When And Where Crossing Over Occurs

Crossing over happens during meiosis I, specifically in prophase I, inside germ cells (in human ovaries and testes: in plants, within anthers and ovules). Prophase I is long and layered:

- Leptotene: Chromosomes start condensing, and the groundwork for pairing begins.

- Zygotene: Homologous chromosomes pair up (synapse) with help from the synaptonemal complex, a protein zipper.

- Pachytene: The big show, DNA exchange, occurs while homologs are fully synapsed.

- Diplotene: The synaptonemal complex dissolves, and chiasmata (the physical signs of crossovers) become visible.

- Diakinesis: Final tightening before chromosomes head to metaphase I.

A few more “where” details I’ve found useful:

- Crossovers aren’t evenly distributed. They tend to occur in hotspots and are rare near centromeres. In humans and mice, a protein called PRDM9 helps specify these hotspots.

- Rates differ by sex. Human females generally have more crossovers on average than males, and the landscape of hotspots can differ between them.

- Mitotic cells usually don’t cross over, but rare mitotic recombination can occur in some organisms and contexts.

So, the setting for crossing over is very specific: homologous chromosomes paired during pachytene, in germ cells preparing to produce gametes.

How Crossing Over Works: From DNA Breaks To Crossover

At the molecular level, crossing over is carefully engineered rather than random chaos. Here’s the simplified storyline I keep in my head:

- Intentional DNA breaks. An enzyme called Spo11 makes programmed double-strand breaks (DSBs) at many sites across the genome during early prophase I. That sounds scary, but it’s a feature, not a bug.

- Processing the breaks. Cellular machinery removes Spo11 and chews back DNA ends to create 3′ single-stranded overhangs.

- Homology search and strand invasion. Specialized recombinases (Rad51 and the meiosis-specific Dmc1) guide one of those single strands to invade the matching (homologous) chromosome, forming a displacement loop (D-loop). This is the handshake that ensures you’re swapping equivalent segments, not random pieces.

- Building joint molecules. DNA synthesis extends the invading strand, and the second end can be captured to form a double Holliday junction. Alternatively, the system can use a pathway (SDSA, synthesis-dependent strand annealing) that typically produces non-crossover products.

- Resolution. Structure-specific enzymes (including the MutLγ complex with MLH1–MLH3, and sometimes MUS81–EME1) cut and ligate the DNA to resolve joint molecules. Depending on how the cuts happen, the outcome is either a crossover (physical exchange of flanking DNA) or a non-crossover (gene conversion without swapping chromosome arms).

- Quality control. Mismatch repair systems fix small sequence differences within the heteroduplex DNA formed during strand invasion. Cytologically, sites destined to become crossovers are often marked by MLH1 foci in pachytene.

Two more rules of thumb I rely on:

- Crossover interference: once a crossover forms, nearby crossovers are less likely, spacing them out along the chromosome.

- Crossover assurance: at least one crossover per homolog pair is promoted, anchoring proper segregation.

In humans, each meiotic cell typically produces a few dozen crossovers in total, on the order of ~25–40, with females generally on the higher end. That’s enough to reshuffle the deck without turning it into confetti.

Linkage, Independent Assortment, And Crossover Patterns

When I first learned Mendel’s laws, independent assortment sounded universal. Then I met linkage. Genes sitting on the same chromosome tend to travel together unless crossing over separates them. The closer two genes are, the less often a crossover falls between them: the farther apart, the more often they’re split up. Crucially, recombination frequency caps out at ~50%, which makes far-apart genes on the same chromosome behave as if they’re on different chromosomes.

A few practical implications:

- Genetic maps: We estimate distances in map units (centimorgans) from recombination frequencies. One centimorgan corresponds to a 1% chance of recombination between two loci.

- Double crossovers: Two crossovers between the same loci can “cancel out” the signal, making distances look shorter unless we account for them.

- Hotspots and coldspots: PRDM9-directed hotspots in humans mean crossovers are not uniform. Some regions light up: others are quiet.

- Interference: Crossovers repel each other locally, so they don’t pile up in one tiny stretch.

Independent assortment still holds cleanly for genes on different chromosomes, and, functionally, for genes so far apart that recombination between them is common. But linkage adds nuance: chromosome position and local crossover patterns shape how traits co-segregate. That nuance is exactly what geneticists from Thomas Hunt Morgan onward used to map where genes sit.

Errors, Health Implications, And How We Study Crossing Over

Because crossing over is so important, the stakes are high when it goes wrong.

What can go wrong:

- Too few or misplaced crossovers: Without the “obligate” crossover, homologs may not separate properly, leading to nondisjunction and aneuploidy (extra or missing chromosomes). Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) is a well-known example, and many early miscarriages trace back to such errors.

- Unequal crossing over: If similar DNA sequences misalign, the swap can delete a segment from one chromosome and duplicate it on the other. Classic examples include some color-vision deficiencies and certain forms of alpha-thalassemia and Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease.

- Abnormal rearrangements: Faulty repair can contribute to translocations or inversions, which, depending on context, can affect fertility or, when occurring in somatic cells, contribute to cancer.

Risk factors and patterns I keep in mind:

- Maternal age effect: In humans, aneuploidy risk rises with maternal age, linked in part to how crossovers were formed and maintained in oocytes.

- Sex differences: Females generally have more crossovers than males, but where those crossovers occur can differ, which influences risk profiles.

How we study it (and it’s pretty cool):

- Classical genetics: Recombination frequencies in flies, plants, and yeast built the first gene maps. Yeast tetrad analysis even tracks all four meiotic products.

- Cytology: Microscopy of pachytene chromosomes shows chiasmata: immunostaining for proteins like MLH1 marks likely crossover sites.

- Population genetics: Patterns of linkage disequilibrium across genomes reveal recombination hotspots and history.

- Direct assays: Sperm typing and single-cell sequencing map individual crossover events: in mammals, sequencing Spo11-bound DNA fragments helps pinpoint DSB hotspots.

Altogether, these approaches let us connect the dots from molecular machinery to health outcomes, and, frankly, make the invisible visible.

Conclusion

So, what is crossing over in biology? It’s the deliberate swapping of DNA between paired homologous chromosomes during meiosis, orchestrated by elegant repair machinery, spaced by interference, and required for both diversity and accurate chromosome segregation. It explains why siblings can be so different, and why the genome isn’t just inherited in big, unbroken blocks. When the process falters, the effects can be serious, but when it works (which is most of the time), it’s a quiet triumph of cellular engineering. Next time you think about inheritance, picture those tiny exchanges during pachytene, deft edits that keep life both stable and surprising.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is crossing over in biology, and why does it matter?

Crossing over in biology is the precise exchange of DNA between homologous chromosomes during meiosis I. When maternal and paternal chromosomes pair, they swap matching segments, creating new allele combinations. This boosts genetic diversity, helps ensure accurate chromosome segregation via chiasmata, and underpins genetic mapping based on recombination frequencies.

When does crossing over occur during meiosis, and where does it happen?

Crossing over occurs in prophase I of meiosis, mainly during the pachytene stage, when homologous chromosomes are fully synapsed by the synaptonemal complex. It takes place in germ cells—human ovaries and testes; in plants, anthers and ovules. Chiasmata become visible in diplotene, and events are unevenly distributed across hotspots.

How does crossing over work at the DNA level?

It begins with Spo11 creating programmed double‑strand breaks. After resection, recombinases Rad51 and Dmc1 mediate strand invasion to form a D‑loop. DNA synthesis and double Holliday junctions follow, which are resolved by factors including MLH1–MLH3 or MUS81 to yield crossover or non‑crossover products. Crossing over in biology is tightly quality‑controlled.

How does crossing over affect genetic linkage and mapping distances?

Genes on the same chromosome are linked and segregate together unless a crossover occurs between them. Recombination frequency estimates map distance in centimorgans (1 cM ≈ 1% recombination) but caps near 50% for far‑apart loci. Double crossovers can mask distance, and interference spaces crossovers so they don’t cluster.

Can lifestyle or environmental factors change crossing over rates?

In model organisms, temperature, nutritional stress, and certain chemicals can shift recombination landscapes. In humans, rates are shaped mainly by sex, age, and genetics (for example, PRDM9 variants). Strong evidence that lifestyle reliably changes rates of crossing over in biology is limited; genotoxic exposures (radiation, some chemotherapy) mostly increase meiotic errors.

Do bacteria or mitotic cells have crossing over like in meiosis?

Bacteria lack meiosis and homolog pairing, so they don’t perform canonical crossing over; their recombination occurs via transformation, transduction, or conjugation. In eukaryotic mitosis, crossing over is generally suppressed, though rare mitotic recombination can happen and cause loss of heterozygosity. Programmed crossovers are a hallmark of meiosis, not mitosis.